Designers are often under pressure to complete a design rapidly so that the tender process can commence as soon as possible. The temptation to “fast track” projects often leads to an inadequate base design, directly increasing the likelihood of disputes. There are often inconsistencies between elements of the design, particularly at key interfaces.

This is not a paywall. Registration allows us to enhance your experience across Construction Management and ensure we deliver you quality editorial content.

Registering also means you can manage your own CPDs, comments, newsletter sign-ups and privacy settings.

Issues then arise over the scope of the original design and who has responsibility for its development or errors in the base design. Often a contractor is its own worst enemy. It wants to be seen as being helpful in keeping the project moving and ends up doing the designers’ job, correcting errors through the detailed design process rather than insisting that the designers resolve the problem.

This invariably results in arguments about whether it’s entitled to a change/variation order or has accepted responsibility for the problem and hence lost the right to claim time as money for its extra work. In an ideal world, many design issues could be avoided by carrying out a comprehensive early review of the design. All too often the adage “a stitch in time saves nine” is not followed and the project suffers.

2. Is the contract being administered properly?

If your contract administrator is ineffective, the allocation of liability agreed between the parties will not function properly.

The contract administrator is responsible for coordinating the contractor and design team, managing documentation, and overseeing contractual mechanisms, such as notifications and assessment of contractor claims.

If the administrator is either too bullish or too lax and not actively taking steps to resolve problems even-handedly and respecting the contractual risk allocation, they can develop into disputes.

To ensure your contract administrator is performing properly, there should be a system of monitoring, review and benchmarking. Employers cannot afford to be passive observers of their appointed contract administrators.

3. Are payment requests keeping step with progress?

If the contractor’s payment applications persistently exceed the certified amount, it’s only a matter of time until the relationship becomes adversarial. Sometimes exaggerated payment claims are a deliberate strategy by low-bidding contractors to boost profits, but often the mismatch reveals an underlying problem: developing claims, disputed variations, or perhaps a supply chain management issue.

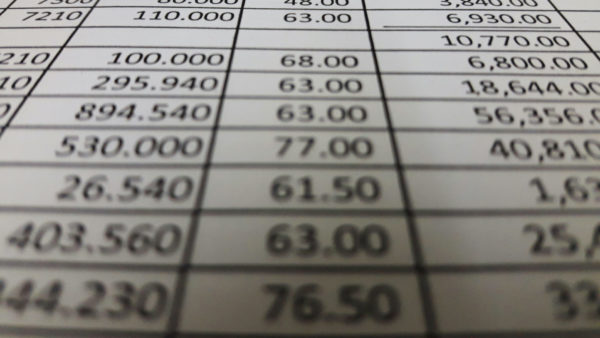

A good starting point is to compare the reported project progress with the history of payment applications, which can reveal whether applications reflect reality and, if so, focus attention on the cost increases to identify early potential claims issues.

4. Do you have a realistic and deliverable programme of works?

The contract programme is a vital management tool outlining a contractor’s approach to completing a construction project. When a project becomes out of sync with the schedule, it is invariably a sign that all is not well. It might be that the contractor committed to an unrealistic programme to secure the contract, or has an ulterior motive to use programme updates to increase entitlements.

Robust early screening of contract bidders and interrogation of proposed baseline programmes and resourcing schedules can often prevent this problem: if a contractor is experienced, reputable and presenting a realistic programme of works for a reasonable price then problems are less likely.

5. Is the contract being followed?

Contracts set out rights and responsibilities, but all too often parties stray from their agreement once a project is under way.

If the contract is left to gather dust, a party could inadvertently limit its entitlement to recovery by, for example, failing to serve notices and follow processes as set out in the contract.

If other parties to the contract start using language such as “not getting contractual” or fail to issue notices and correspondence required by the contract, then alarm bells should be ringing. Similarly, if one party sends far too much correspondence to the other party, this can indicate a plan to obstruct the normal working of the contract.

Bob Maynard is head of construction and engineering disputes at Berwin Leighton Paisner