The recent case relating to the Robin Rigg offshore windfarm (MT Højgaard v E.ON Climate & Renewables) provides a warning for anyone intent on holding tight to complexity in our contracts. The £23.3m dispute hinged on the court interpreting a series of “diffuse” contract documents.

The windfarm contract was described by the judge, with a hint of criticism, as having multiple authors, containing loose wording, and including ambiguities and inconsistencies. The contractor accused the client of tucking away onerous provisions in technical requirements, rather than spelling them out clearly and simply in the contract conditions.

This is not a paywall. Registration allows us to enhance your experience across Construction Management and ensure we deliver you quality editorial content.

Registering also means you can manage your own CPDs, comments, newsletter sign-ups and privacy settings.

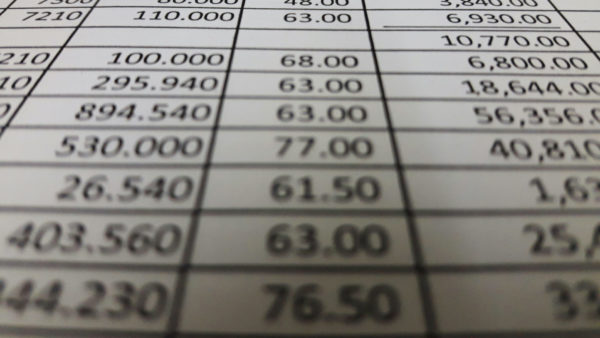

Simplicity could have helped the client describe the functionality it expected – and helped the contractor to understand what works had to be delivered. Instead, the contract writers added layer upon layer of quality standards, performance specifications and technical requirements, with at least eight different measures of quality.

Those measures reflected both inputs, including professional manner and good industry practice, and outputs, such as meeting an international standard and having a design life of at least 20 years. Some of these were met, others were not. One single functional standard, relating to design life, proved very costly indeed for the contractor.

The longer a contract is, the less likely it is that any single person will read all the documents which together describe the parties’ agreement. Lawyers won’t read the project specification because of too much technical jargon; specialists won’t read the conditions because of too much legal jargon.

But even when a contract is inelegant, clumsy or badly drafted, someone – in the Robin Rigg case, the judge – has to work out what it actually means. Surely working out what you’ve signed up to is better done before – not after – you’ve carried out a project? Otherwise you might as well click “I agree to the terms and conditions” knowing full well that you haven’t got the foggiest what those terms and conditions actually say.

For clarity’s sake, so that you know what you are signing up to, keep contracts simple. But as our current standard forms are clocking in at over 20,000 words, whether we can or will is doubtful.

Sarah Fox is a lawyer and founder of contracts business 500 Words